By Susan Greene

“The globe shrinks for those who own it; for the displaced or the dispossessed, the migrant or the refugee, no distance is more awesome than the few feet across borders or frontiers.” –Homi Bhabha

The MAIA Mural Brigade had a 5 day orientation throughout the West Bank and ’48 (Israel). We visited with many people and saw many faces of the occupation including: Silwan, Hebron, Nazereth where we visited Al-Birwa village which was demolished in 1948; Dheisheh Refugee Camp, Bethlehem; and more.One very poignant visit was with the Aamer family who lives in Mas’ha village in the West Bank. I was first introduced to the Aamer family in 2004 by Kate Raphael from the Women’s Peace Service. In 2004/5 the Aamers were excited to paint a mural on the wall that surrounds them on 4 sides and that cuts them off from their village. They told me how participating in the mural had given their children hope and decreased their feelings of depression. It is now 6 years later, and I have arranged to bring the MAIA Mural Brigade for a visit. I feel very moved to see the Aamers again. Hany Aamer said in 5 years the new trees that they have planted in front of their house will be tall enough so they will not see the wall anymore from their front door. The mural has faded dramatically and I offer to refurbish it. The Aamers said ‘No.’ They no longer want the mural. Now they see it as an attempt to make something awful into something beautiful. Here is their story.

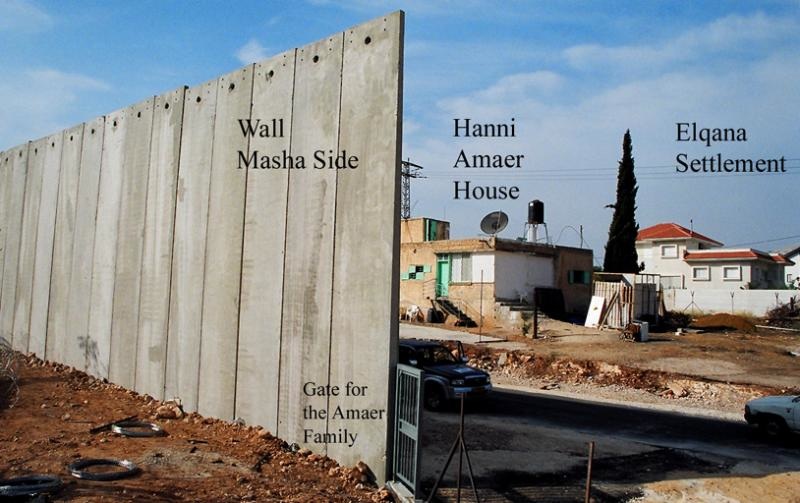

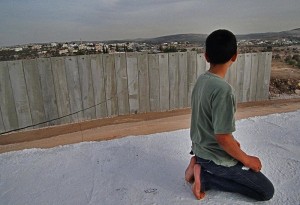

Maisa, Assia, Ishak, Nidal, and Shaad Aamer have looked out their front door and instead of seeing their garden, animal shed and beyond to their village, they are confronted by an enormous, gray, concrete wall. In the village of Mas’ha, West Bank, Palestine, the children of Hani Aamer live surrounded on all four sides by the Apartheid Wall or Separation Fence, depending on one’s perspective. Although the wall running through Mas’ha is actually a fence topped with barbed wire, in November 2003, the Israeli army erected a concrete section, twenty-four feet high and one hundred twenty feet long, directly in front of the Aamer home. This was the Israeli response when the family refused to accept a blank check to move from their land. An Israelisettlement comes right up to the back of the property, a mere twenty feet away.

The Aamer home sits between the two main gates into the village. Family members are forced to let themselves and others in and out through a locked gate, which sends an alarm to the Israeli army every time it is opened. For nearly a year, the Aamers did not have their own key to the gate, nor were they allowed visitors. The family was threatened with home demolition if they violated the order. After their situation was publicized on Israeli television, the army commander agreed to let the Aamers have a key to the gate and, with prior Israeli army approval, periodic visits from family members.

I met the Aamer family on July 18, 2004. Sponsored by the International Women’s Peace Service (IWPS) my partner Eric Drooker and I arrived in Mas’ha as volunteers for Break the Silence Mural Project. We were very curious to meet this family and planned to ask if they would be interested in painting a mural on the wall that cut through their land. To this first meeting, we brought art supplies and conducted a drawing project with about fifteen neighborhood youngsters while their parents looked on. We asked the children to draw pictures of their hopes for the future and then asked the parents what they thought about a mural. “Yes!” was the instant response of Munira, the mother of the family, and Hani, the father, also immediately agreed. They told their excited children that we would soon return to paint with them.

A few days later, Eric and I—joined by IWPS and members of two Israeli organizations, Anarchists Against the Wall and Black Laundry—met at the gates to the Aamer house and stopped at the red sign that threatened: “Warning: Mortal Danger for Damaging the Fence.” Israeli soldiers and settlement police arrived quickly and questioned us all. “Are you going to paint on the wall?” “No, we are doing an art project with the children, but, you know how children are…” The soldiers collected all our passports, said they must obtain permission for our visit, and noted that because our group included Jewish Israeli citizens, they had a particular obligation to protect our safety. They retreated to their jeeps, and when they were a safe distance away, we discussed the irony that at this exact spot just months earlier, Israeli soldiers had shot an unarmed Jewish Israeli protester with live ammunition. Twenty agonizing minutes later, the soldiers returned the passports, and the Aamer family was allowed to open the gate.

A few days later, Eric and I—joined by IWPS and members of two Israeli organizations, Anarchists Against the Wall and Black Laundry—met at the gates to the Aamer house and stopped at the red sign that threatened: “Warning: Mortal Danger for Damaging the Fence.” Israeli soldiers and settlement police arrived quickly and questioned us all. “Are you going to paint on the wall?” “No, we are doing an art project with the children, but, you know how children are…” The soldiers collected all our passports, said they must obtain permission for our visit, and noted that because our group included Jewish Israeli citizens, they had a particular obligation to protect our safety. They retreated to their jeeps, and when they were a safe distance away, we discussed the irony that at this exact spot just months earlier, Israeli soldiers had shot an unarmed Jewish Israeli protester with live ammunition. Twenty agonizing minutes later, the soldiers returned the passports, and the Aamer family was allowed to open the gate.

The children run up to us, shaking our hands and saying hello. They asked in English: “How are you?” and “What’s your name?” Tea was served, and Eric and I started mixing bright colors. Without any prompting, and despite the army Jeep sitting outside the fence twenty yards away, the children joyfully and vigorously started painting on the wall–fish, a large bird with a snake in its mouth, hills, flowers, several bright yellow suns, trees, faces, and many, many houses. Eric painted a phoenix in flight. More than twenty children painted with us. Then their parents and neighbors joined in. Eric and I somewhat nervously watched the Israeli army as they watched us the whole time. At one point, a Jewish Israeli settler stood outside the gate conversing with the soldiers and watching, then finally left. We worried that at any moment they would stop us. We were putting a lot of paint on the wall. At about 2 p.m., Hani Aamer came back from his fields with his cart and donkey. To get into the enclosure, he had to open the larger gate, to which he had no key. We watched as the soldiers opened the gate for Hani to enter his property. Hani’s kids ran up and jumped on the cart for a ride. Soon after, the Israeli soldiers came in and told us they wanted us to leave immediately.

We packed up our paint and went inside the house for one more cup of tea.

Now, when they looked out the front door, the Aamer family would see a yellow and orange phoenix rising up from an almost psychedelic green valley dotted with red flowers, brilliant suns, large animals and houses. Of course, the wall was still there. The IDF and settlement were still there. But the view from the front door of the Aamer family home had begun to change, recording the family’s engagement in a collaborative public act of creative resistance and solidarity.

Now, when they looked out the front door, the Aamer family would see a yellow and orange phoenix rising up from an almost psychedelic green valley dotted with red flowers, brilliant suns, large animals and houses. Of course, the wall was still there. The IDF and settlement were still there. But the view from the front door of the Aamer family home had begun to change, recording the family’s engagement in a collaborative public act of creative resistance and solidarity.

A week after the painting party, I returned to the Aamer family to interview them. I had a research grant from the Palestinian American Research Center to analyze what public art projects such as this one mean to all the participants. Would it be possible to determine the effects of the project? What did solidarity mean in this context? The mission of Break the Silence Mural Project includes using culture to bring back stories of Palestine to an American audience. What did the project say about the Aamers’ life? What did it mean to the family to work with Jewish Americans and Jewish Israelis? What did it mean for me, a Jewish American, to collaborate on public art projects with Palestinians?

Munira Aamer said, “The wall continues to be a wall, but the mural has made it easier for us to look at it. The mural creates some pleasure and relief for me and my children. The mural changed the view–now I am looking at something alive, and before I saw it as the end of the world, a disaster. Now when I look at it, I see birds, suns, and flowers. This view is beautiful and good. Before it was only scary. My children are very happy and proud of their painting in the mural. My kids see life when they see the mural. The mural was like opening a window for the world. One day the wall will be demolished. I wish I could open this cage and fly with my children, like the free bird in the mural.”

Munira Aamer said, “The wall continues to be a wall, but the mural has made it easier for us to look at it. The mural creates some pleasure and relief for me and my children. The mural changed the view–now I am looking at something alive, and before I saw it as the end of the world, a disaster. Now when I look at it, I see birds, suns, and flowers. This view is beautiful and good. Before it was only scary. My children are very happy and proud of their painting in the mural. My kids see life when they see the mural. The mural was like opening a window for the world. One day the wall will be demolished. I wish I could open this cage and fly with my children, like the free bird in the mural.”

Hani Aamer said: “When the Israeli government started building the wall, many people from all over the world came to support our resistance to it. The government arrested or took all of the supporters and deported them. The Israelis told me that the people who came to help me were no longer here. They said: “You are now alone. Who is going to help you?” But the solidarity people, including Israeli solidarity people, came back to help us again. It lifted my spirits when the solidarity people came back to paint on the wall. My kids started to play outside again. For a year, they were so sad they would not play outside. When you come to paint with the children, it makes them feel like they can live.”

Munira Aamer continued, “The children remember who painted with them on the wall, and they remember the experience of painting with their friends. When we look at the wall, we remember who painted each section and how it felt to paint together.”

The family asked when we would return to finish the mural. The painting had only gone up to where a six-foot ladder allowed. Two-thirds of the wall was still unpainted concrete, in stark contrast to the colors of the mural at the bottom.

“People who come by want to know why the painters didn’t finish. They say the mural should cover the whole wall,” Munira said. “The people who came and worked with us value the ideas of the mural—that is good and we hope that they will cover more of the wall.”

And so the next summer, 2005, we returned to the Aamer home to finish the mural. Together with the family and their friends, a group of young Palestinian women activists called Flowers Against the Occupation, members of the IWPS, and Anarchists Against the Wall, we prepared to paint the sky. The first day, the painting continued until about 2 p.m., when the Israeli soldiers intervened. They invaded the yard barking orders and asserting their power with sub-machine guns. We tried to argue with them, as did some neighbors of the Aamer family, to no avail. There was a palpable sense of, anger, frustration, and resignation among the Palestinians. A neighbor, standing on the porch in close proximity to several Israeli soldiers, angrily threw down her cup of tea. Several of the men present whisked her away, then negotiated frantically with the Israeli soldiers, who decided to let it go.

And so the next summer, 2005, we returned to the Aamer home to finish the mural. Together with the family and their friends, a group of young Palestinian women activists called Flowers Against the Occupation, members of the IWPS, and Anarchists Against the Wall, we prepared to paint the sky. The first day, the painting continued until about 2 p.m., when the Israeli soldiers intervened. They invaded the yard barking orders and asserting their power with sub-machine guns. We tried to argue with them, as did some neighbors of the Aamer family, to no avail. There was a palpable sense of, anger, frustration, and resignation among the Palestinians. A neighbor, standing on the porch in close proximity to several Israeli soldiers, angrily threw down her cup of tea. Several of the men present whisked her away, then negotiated frantically with the Israeli soldiers, who decided to let it go.

It was unclear whether we would be permitted access the following day, but a different crew of soldiers was at the gate and they were polite, stopped us for a while, then permitted us to enter. They seemed unaware of the previous day’s events. Children poured into the area joyously, many more than the day before, as word had spread that the American painters were back. We continued to paint the sky while drinking many rounds of tea.

At around 2 p.m., Hani Aamer phoned to say the painting had to stop immediately. We had no idea why, but knew that if Hani said we had to go, it must be serious. Later, we learned that because of the “disengagement” of settlers from Gaza taking place at that moment, the Israeli army perceived the mural painting as a provocation to the nearby Jewish settlement. The IDF had threatened Hani with taking back the family’s key to the gate if we did not leave immediately.

Hani Aamer later explained his dilemma. “The soldier is telling me that the visitors should leave. They are my visitors who come to support me and stand in solidarity with us and I cannot tell them to leave. They come from England and the United States. They are guests in my house. I cannot throw them out.” Yet Hani Aamer had to do just that. This act of the Israeli army commander forcing Hani to ask his visitors to leave, instead of ordering us to do so himself, was an infliction of additional pain. For Hani, treating guests in a rude or inhospitable way was completely unacceptable and humiliating, especially guests who had come from so far.

We packed up our materials, leaving the leftover paint and brushes behind for the Aamer family. After a final defiant cup of tea, we left the premises. We had planned a mural opening the following day, but since the mural was not completed, we held a press conference instead. Very few reporters showed up, in part because everyone was focused on the forced removal of the settlers from Gaza. We took advantage of the time and opportunity to interview Hani. Someone suddenly appeared and urged me to follow quickly.

I ran back to the gate, and Munira let me in. This was the first time I had been on the Aamer property without a large group present. I had an immediate and shocking sense of what life was like for this family. It was eerily quiet, and sounds echoed off the concrete wall. I now understood much more clearly how cut off the Aamers really were from the village of Mas’ha and their community. They had been relegated to a bizarre existence in which they were much closer to and in full view of an illegal Israeli settlement. The settlement’s inhabitants were armed and often directed violence at the family, such as breaking windows and destroying the chicken coop. Munira and I went inside her home, and I saw that she had not, despite Israeli military orders, stopped painting the day before. Beginning with the sky blue from the mural, she had begun to paint the rooms of her house. She had started with a bedroom and painted the ceiling and walls. The morning light streamed in and the room was glowing. As I stood in the living room, I could see both blues, of the mural and of the bedroom, from my peripheral vision. The project of solidarity, resilience, and resistance had moved from outside to inside the house. Munira Aamer had refused to stop painting and she was very pleased with her efforts.

Now in 2011, the Aamers refused my offer of touching up the mural which has faded. They say the mural now seems to them an attempt to make something horrid beautiful. They asked for help to paint the mural out. They said they would like people to write poetry on the wall about how they feel about the wall and freedom. They do opt to keep the firebird that Eric painted! So on my very last day in Palestine, I made my way to Mas’ha and bought several gallons of white paint. Under the strong sun I helped Hani and Munira paint out the mural.

Now in 2011, the Aamers refused my offer of touching up the mural which has faded. They say the mural now seems to them an attempt to make something horrid beautiful. They asked for help to paint the mural out. They said they would like people to write poetry on the wall about how they feel about the wall and freedom. They do opt to keep the firebird that Eric painted! So on my very last day in Palestine, I made my way to Mas’ha and bought several gallons of white paint. Under the strong sun I helped Hani and Munira paint out the mural.